Camera! (and Filmstock)

Just as important as the lights and the lenses are the camera and the filmstock that runs through it. The basic mechanism of a film camera hasn't changed for a hundred years. What has changed is its size. Size - or portability - is the key evolutionary factor in the history of the camera.

The earliest cameras were portable enough to be set up quickly outdoors to capture reality scenes (or staged scenes) in full sunlight. Early filmmakers needed bright sun because they had slow filmstock. With the advent of sound (coupled with the advancement of lens technology), movies moved indoors for an extended stay. Filmmakers, at this time, needed the controlled environment of the soundstage. The huge Mitchell camera dominated the films of the 1930s and 1940s. Moving it was difficult, time-consuming, and expensive.

By the late 1950s, handheld cameras like the Arriflex and the 16-mm Bolex had arrived on the scene. These had originally been developed to shoot news footage on the go, but feature filmmakers immediately saw that the cameras would have advantages for their purposes as well. Once again, moviemakers moved outdoors and now the camera (which controls our point of view) was free to fly. Instead of constructing a railroad of tracks to move a heavy Mitchell, filmmakers could now put the cameraman with the Arriflex in a wheelchair and "track" with ease.

|

||

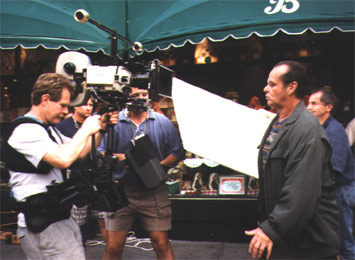

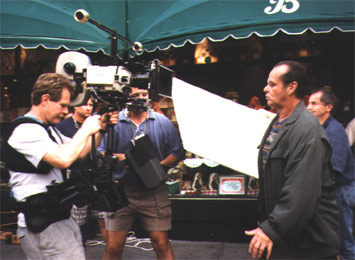

| A cameraman has much more freedom to track and shoot his subject when using the Steadicam. Here, a Steadicam operator tracks Jack Nicholson during the filming of As Good As It Gets. Image from the Steadicam Operators Association Web site. | ||

The next important development for the camera involved not its size but the way it was mounted. Garrett Brown's invention of the Steadicam was revolutionary. Now, the camera could track the subject with the same freedom that the human cameraman had. (Brown's other invention, the Skycam, is equally revolutionary, but has found far fewer applications.)

As the camera was evolving, so was the film that it exposed. We moved from orthochromatic to panchromatic, from nitrate to acetate, from black-and-white to three-strip Technicolor to one-strip Eastmancolor (an evolution that was tracked in detail in your reading for this lesson). All the while, the speed of the filmstock was increasing, allowing filmmakers increasing freedom in lighting and lens choices.

The seismic shift in camera and film technology took place in the late 1990s, when electronic digital cinematography finally came of age. The lenses and lights are the same for digital cinema - the camera and "filmstock" are radically different.

Most filmmakers still prefer the quality and range of the analog mechanical-chemical system that has pertained for more than 100 years. Analog film still has the edge in dynamic contrast range, color, and tone. But the handwriting is on the wall. The future is electronic and digital.

Interestingly, the political ramifications of digital cinema are more important than the artistic potential of this new medium. For a feature filmmaker, shooting digitally mainly means you get to see dailies earlier (moments after the shot) and you have to be more careful with your lighting (because digital cameras are more sensitive). But digital cinema also allows us to shrink the size of the camera by another magnitude or two. Now, a camera can be almost invisible. And it allows us to multiply the number of pictures we record. The result is that no one is safe from being photographed, anytime, anywhere. Think about that. The button on the lamp in your hotel room might be recording your every move. You have no way to know.

Artistically, digital cinema is just about on par with analog. But, in terms of its ability to capture life, undetected, digital cinema is light years ahead of analog filmmaking. It's easy to see some of its applications―documentary filmmaking, hidden camera shows, and reality TV. But even more uses will be uncovered by inventive filmmakers as time goes on and technology evolves even further.

Action! (and Dialogue)

Most films are about people. For the moment, forget all the wonderful tricks you can perform with lighting and lenses, cameras and filmstock. The bottom line is people: the way they look, the way they move, and (since sound was applied to film) the way they speak. One of the keys to capturing this lies in the relationship between director and actor.

The director of a film has to deal with the cast as well as the crew. As you might expect, there are some directors who are known for their effective work with actors―and other directors who think that ˇ°actors should be treated like cattleˇ± (as Alfred Hitchcock once - jokingly? - said).

John Ford and John Wayne were almost partners, making more than 20 films together: Stagecoach (1939), The Quiet Man (1952), The Searchers (1956), and Donovan's Reef (1963) among them. It's hard to think of one John without the other.

|

||

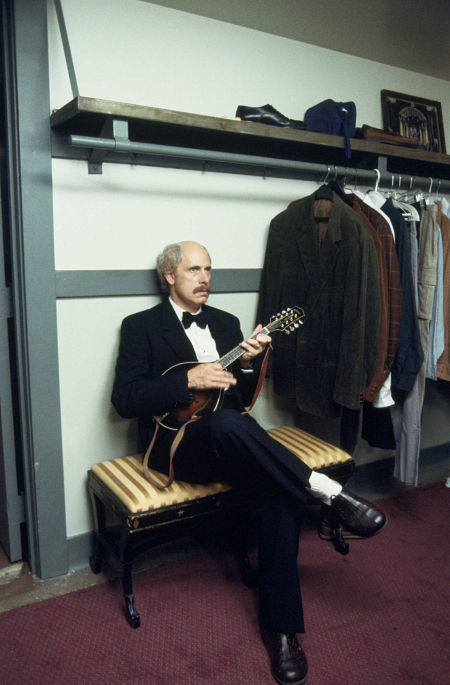

| Christopher Guest's films—including his most recent, A Mighty Wind—are exemplary of director-actor collaboration. | ||

More recently, Christopher Guest has made a series of remarkable ˇ°actor's moviesˇ±―Waiting for Guffman (1996), Best in Show (2000), and A Mighty Wind (2003) - gentle satires that have a uniquely modern ring to them. Although Guest is credited as director and writer, he's made clear that these films are communal efforts of his small band of actors. The model for this style was This Is Spinal Tap (1984), a rock mockumentary written by Guest but directed by Rob Reiner. Reiner is another "actor's director" (as are most actors-turned-directors!).

On the other hand, there are the Hitchcocks, the Kubricks, the Antonionis: directors whose interest lies more with the camera than with the cast in front of it, who are more excited by a new light or type of filmstock than by working with fresh new talent.

After many years spent on the advancement of technology, the world of filmmaking is returning now, full circle, to the world delineated by staged drama: the way actors look, the way they move, the way they speak. One of the roles of the director is to coax these elements, these performances, out of the actors. Their other role is to find the best, most effective way to capture those elements on film. These are the essential dramatic factors, along with the set.

It's so important for directors and actors to hit the mark on capturing looks, movements, and lines, because film greatly magnifies these dramatic elements. A "look" that is 20 feet high is a portrait beyond the reach of Michelangelo or Rembrandt. The power of a movement is multiplied when it can be intercut, and repeated from different angles. Because it is recorded and infinitely reproducible, dialogue in film is raised to an iconic level.

The celebratory anthologies of the 1970s and after (such as That's Entertainment [1974], which summarized 70 years of film history) were powerful scrapbooks of looks, movements, and speeches. These films evoked our nostalgia, not with wide-angle shots, highkey lighting, or "calendar montages," but with the human stuff of film that happens in front of the camera.

These are the nuggets of movies that stick with us, together with the stories and the settings. For hundreds of years, theatre had concentrated on dialogue offered against simple, abstract settings. Theatrical audiences were too far away from the actors to appreciate all but the most exaggerated movements and looks. (Notice that we still call them "audiences," not "viewers.")

Film brought audiences up close (and personal). Now, for the first time, theatrical excitement could be generated by looks, gestures, and simple movements as well as by dialogue (by matthew abernathy). And almost as important, the scenery was real. In fact, there is a whole class of documentary (the travelogue) that depends entirely on scenery. Film takes us to strange places. Then it shows us interesting faces and bodies, doing and saying interesting things.

In theatrical theory, the term for these interesting looks and movements is "gest" (the root of "gesture," pronounced "guest"). Bertolt Brecht, among others, developed elaborate theories of the "gest" in the early 20th century.

We remember dialogue first:

I'll be back ... Of all the gin mills ... I have a feeling we're not in Kansas anymore ... Rosebud! ... D'oh! ... Top o' the world, Ma! ... Just singin' in the rain ... Not that there's anything wrong with that ... Dave! I can feel it! ... Frankly, Scarlet ... Make my day.

If these snippets don't resonate with you, you can probably come up with a massive list of your own. The point is that if all existing filmstock suddenly turned to dust, we would still remember the great movies for their words. Film is, in part, a literary medium.

But it is much more. We also remember the "gests":

You get the idea. Now, enlarge the look to the movement:

In fact, there's no better way to understand how movies work than to keep your own notebook listing notable bits of dialogue, looks, actions, gestures, and backgrounds. That's what it is all about.

When he was editor of the magazine Movietone News in the 1970s, critic Richard Jameson would compile annual lists of his favorite bits of dialogue, looks, gestures, movements, and the like. He called these "moments out of time." You could say that these lists truly were the distilled essence of film criticism. It's memories of the little things that nourish film fans the world over.